— Louise Bourgeois

The town of Vardø, a small settlement on a butterfly-shaped island joined to the Norwegian mainland by an undersea tunnel, is at a latitude sufficiently lofty to place it east of Istanbul. It’s the only European town to rest in the Arctic climate zone – from November to February, it’s plunged into unending night, while in summertime, the sun never sets. There are no trees this far north; a landscape of rock, moss, cloud, sky and sea is both infinitely varied and unremitting. Fishing once made this a thriving port, though those days are long gone. Even with daily air and sea connections to the Arctic capital of Tromsø, it is remote, a frontier town.

It’s a curious site to commission a collaboration between one of the world’s most famous artists, the French-American Louise Bourgeois (in what was to be her last major work before her death in 2010) and the Pritzker Prize-winning Swiss architect, Peter Zumthor. The Norwegian government, in all its cashed-up liberal glory, embarked upon a program of building lookouts, museums, shelters and trails along a tourist route, but the project in Vardø, a memorial, was starkly more ambitious, in both its intent and its chosen creators.

During the 17th-century – under the guise of post-Reformation religious zeal, but more likely in an attempt to rest economic and social control of a region marked by its resistance to borders – over a hundred women, girls and Sami men were tried for witchcraft. Below the town’s church, by a rocky beach overlooking the Barents Sea, 91 were subsequently burnt at the stake. After some three and a half centuries, it was decided that these victims of a state-ordained terror should be remembered.

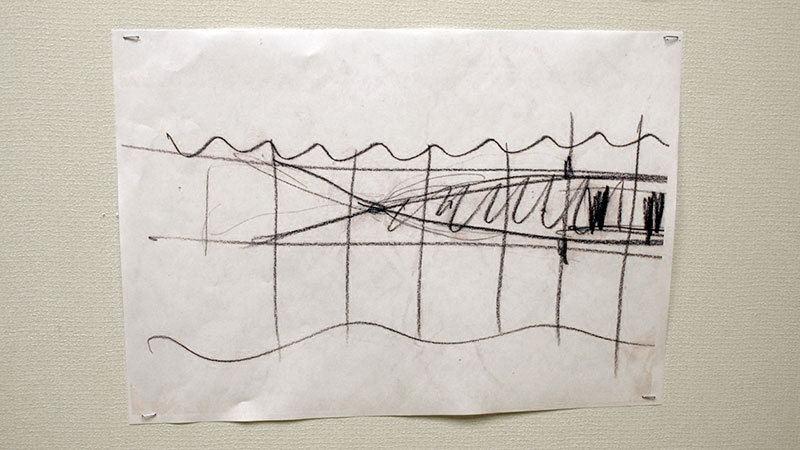

Zumthor’s brief was to come up with something to house Bourgeois’ memorial installation. What ensued tests the limits of collaboration: after he sent her an initial design, she sent back her ‘reaction’ to it, and deciding that his structure was complete, asked Zumthor to create a distinct building for her work. Zumthor then deferred, offering to discard his original structure, but Bourgeois replied, ‘No, please stay’. The two resulting buildings form what the architect calls a ‘line and a dot’. Zumthor’s Memory Hall may have such been relegated to the role of explicatory straight man to Bourgeois’ conceptual punch line, but it’s none the less fruitful a conversation.

The Memory Hall sits within a lineage of post-WWII memorial making, one that attempts to anneal atrocity by conjuring reason, be that mathematical precision or the elemental force of natural materials. Zumthor’s sensitive way with wood has been a feature of his career; here it is employed to form a 125-metre long exoskeleton that recalls the disused fish-drying frames that dot the island. It’s an arresting structure, formal and elegant but also defiantly non-monumental with a lightness, a sense of impermanence. A taught innard of fabric, outwardly sail-like, pale and hardy, is accessed by a wooden platform. While not entirely sheltering visitors from the none-too-considerable elements, the silk-clad corridor is shadowy, disconcertingly enclosing. Banners bearing the women’s names and horrifying trial testaments propel visitors forward along, the gloom punctuated by a series of 91 windows, one for each killed, each hung with a bare light bulb. Anyone who has visited Scandinavia, Arctic or otherwise, will be familiar with the winter ritual of the lit window; Zumthor inverts its implication of welcome, warmth and familial comfort. Instead we peer back in time to a community that has turned upon itself.

While Zumthor plays nice with precise contrition and contemporary witness, Bourgeois violently ruptures all that comes before. The Damned, The Possessed, The Beloved is a torture porn movie set of brute literality, less about remembering or honouring, more about a transfer of fear and dread from historical document to the physical, to consciousness. Within Zumthor’s dark glass box is a small metal chair, its seat shooting a dense thicket of flame. In the manner of Bourgeois’ earlier cells, it is surrounded by a number of mirrors. Interrogatory, screen-like, they project, magnify and distort, seemingly to infinity. The flames twist and flicker, conjuring the women’s alleged ‘glamouring’ and lycanthropy. The perpetual flame – that old chestnut of commemoration and reflection – here is devoid of any redemptive quality, illuminating only its own destructive image. The visitor momentarily exists in the darkness of what has taken place.

Norway’s response to a more recent incident of unimaginable horror – Breivik’s Oslo bombings and bloody rampage on Utøya – was measured and dignified. Similarly, in Vardø, the country’s willingness to illuminate such terrible acts, even those beyond memory or reparation, speaks volumes about national tolerance and fortitude. The Steilneset Memorial, in all its cosmopolitan improbability, is fittingly a work of immense conceptual and aesthetic courage.

Submission for the Gertrude Contemporary & Art and Australia Emerging Writers Program 2012