– Rudolf Stingel

Nominally Italian since the post-WWI carve-up of the fallen Austro-Hungarian empire, the Tyrolean city of Meran, Rudolf Stingel’s hometown, was the hot Hapsburg destination, a leafy valley Shangri-La teeming with poets, adulterers, gamblers and the ailing. A frequent visitor was a young Austrian doctor, the soon-to-be father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. In 1900, he took a mysterious trip there with his sister-in-law, obliquely referred to in On Dreams, where, like Bryan Ferry, he muses on the price of love. Lest he ‘be obliged to betray many things which had better remain my secret’, he forthwith declined to spill the beans.

Even if you’ve been fortunate enough to see one of Rudolf Stingel’s earlier ‘carpet’ works, it’s scant preparation for the ambush of his recent monographic show. This is the first time that François Pinault’s 18th-century Venetian pile has been given over to one artist and Stingel does indeed take it over, the work installed and unfolding over the palazzo’s entire 5000sqm. As the artist’s New York carpets did (be they the orange shag pile or the kitsch casino floral), the atrium’s wall-to-wall immediately evokes place. An antique oriental, the traditional, highly decorative Turkish patterns are essentially unaltered, albeit photographically reproduced, magnified and rewoven in a factory. Yes, it speaks to the mercantile and maritime glory of the Venetian Empire all about, but it also catapults you headfirst into fin-de-siècle Vienna.

While the atrium more than hints as to what’s in store above, it’s once you’re up the carpet-covered stairs that things get, well, complicated. Not only does the carpet cover the floor, but also the walls, its intricate patterning relentlessly repeating and intersecting across and with the palazzo’s equally intricate spaces. The effect is disconcerting, stifling: Sigmund’s couch has metamorphosed, metastasized and there’s nowhere to hide.

Stingel has been producing monochromatic abstract paintings on canvas since his move to New York in the late 1980s and a number of large silver-toned oil on enamel works are hung on the first level. His ‘classics’ often function as ciphers – the artist once produced a how-to manual, an act of savvy branding, yes, but also a way of deriding the transcendentalism of American abstraction. Here the ethereal surfaces, a Fortuny silk’s shimmer or lagoon’s silvery moonlight, provide a still point in the relentless patterning, as well as some pleasing Venetian mise-en-scène. But, more importantly, they also offer up a mirror’s blank tain to the large representational work above and below.

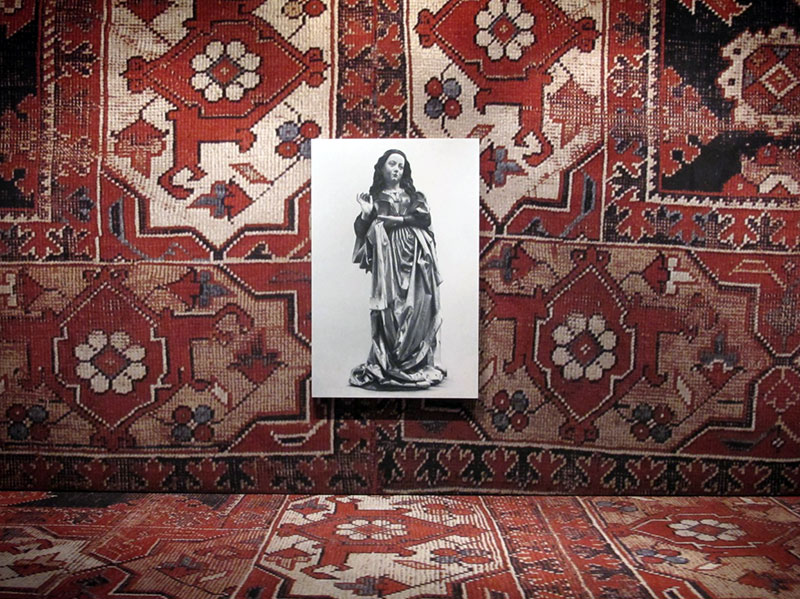

On the next level hangs a series of oil on linen ‘portraits of sculptures’. These photorealist depictions of wood carved Südtirolean religious figures – saints, martyrs and cautionary skeletons – conjure illustrative plates from old art history texts. Stingel has said he likes to question art’s ability to inspire awe. This might seem disingenuous given the scale of the work at Palazzo Grassi and the constant toggling between dread and wonder that it provokes, but indeed the faces that populate the upper galleries and labyrinthine, hermetic backrooms are neither awe-struck nor awe-inducing. In New York his ‘sculpture paintings’ were seen as an act of humility in the face of faltering mammon; here they form a touchingly quotidian chorus, a lineup drawn from distant memory. Small, tightly cropped, the snapshot focus on facial features or quirky hand movements appears to rescue each from their theocratic day jobs, their thrall to a vindictive Mediaeval God. Stingel returns them their humanness.

The shows key work, an imposing portrait of late Austrian artist Franz West, hangs in the correspondingly magnificent piano nobile, where you can be in no doubt this is Venice – the Grand Canal is right outside and the ceilings drip with 18th-century bling – no matter how much Vienna might be on your mind. Stingel’s friend and fellow artist gazes beyond you, to a city that itself seems to exist outside of time. The canvas is grimy, splattered, studio-worn, which may or may not be intentional. (Stingel said that he accidentally left it on the floor after completion, but also concurred that a work that contested paintings usual expectation of reverence would have pleased West.) Back down in the atrium is another grisaille work, this time a self-portrait, lurking self-deprecatingly in the shadows of an internal loggia, easily missed. West’s may be no pristine tribute, but Freud’s uncharacteristically soothing notion that ‘those who love have, so to speak, pawned part of their narcissism’ appears in play.

Stingel’s schtick might be painting about painting, but at the same time, he is not a painter’s painter. His paintings are sometimes carpets, and while many of his paintings are indeed paintings, they are also often ready-mades, or paintings of photographs or paintings of photographs of sculpture. His photorealist paintings don’t seduce stylistically, instead they function as snapshots, their casualness at odds with their scale. His abstract paintings may be things that many people (garden-variety Venetian day-trippers, school kids, off duty art critics) like a painting to be – technically tricksy, conceptually solid, thematically undemanding and seductively pretty – but in the face of easy devotion he pleads with us not to respect them, not to trust him too much, not to ask him to let you in on the secret.

Drawn from Pinault’s and the artist’s own collections, as well as work created specifically for the site, the show isn’t a retrospective – there’s no Stingel styrofoam or tinfoil or cellotape, no Stingel jokey nowness or newness. Instead, the artist, church-going Südtirolean boy turned young Viennese-trained classical portraitist turned mid-career New York conceptual art star, re-anchors himself in the Mittle-European, his Freudian hall of mirrors a homecoming, an introspective culmination of his oft shifting practice. Set loose in the threadbare weft and weave of the unconscious, you can’t be sure if you’re playing analyst or it’s you being analysed. Empires, ideologies come and go, Stingel seems to be saying, as does representation and abstraction. As do secrets and stories, as do we.

Rudolph Stingel at Palazzo Grassi

July 4 to 31 December, 2013

Submission for Frieze Writer’s Prize 2013